How does one know thyself? When confronted by the realities of our station in life, how do we respond to them? Will we take advantage of what time we have left to fulfil the passions that burn within us?

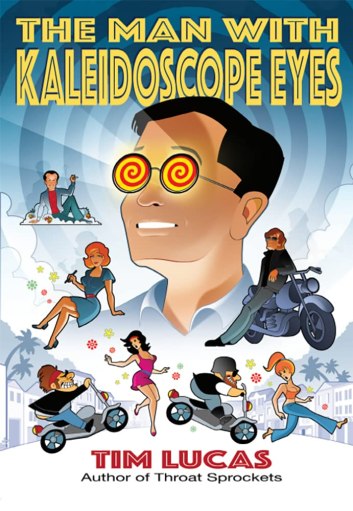

These questions percolated in my mind as I read Tim Lucas’ novel The Man With Kaleidoscope Eyes, a fictionalized account on the making of Roger Corman’s 1967 psychedelic opus The Trip – which first appeared in cinemas on this day 55 years ago.

The Subject

By the mid-1960s, Roger Corman, a top-tier producer/director for B-movie studio American International Pictures (AIP), had become dissatisfied by the constraints of his series of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations starring Vincent Price. Endeavouring to make films that reflected the controversies of the times, his first attempt at such a movie, The Wild Angels (1966) – a biker drama starring Peter Fonda, Nancy Sinatra, and Bruce Dern – was a major box office success. For its follow-up, Corman turned his attention to a particularly hot-button subject: lysergic acid diethylamide, better known as LSD or acid.

Directed from a screenplay by a long-time member of Corman’s talent pool, Jack Nicholson – better known today for playing a certain Clown Prince of Crime! – the resulting film, The Trip, follows disillusioned commercial director Paul Groves (Fonda) as he seeks to gain personal insight through an LSD trip: the first of its kind depicted in a motion picture. Guided by his guru friends John (Dern) and Max (Dennis Hopper), Paul witnesses a parade of sensual and terrifying imagery throughout his hallucinogenic odyssey that forces him to consider his place in the world, and especially his relationships with women; he is torn by his feelings for his wife Sally (Susan Strasberg), who he is soon to be divorced from, and Glenn (Salli Sachse), an acquaintance of Max’s with whom he feels a mutual attraction.

Alternately confounding, nauseating, sexy and funny, The Trip remains a thoroughly engrossing watch, marked by its rapid editing and depictions of nudity, both of which were considered ground-breaking for the time. Although its style and subject matter reflect key interests of the hippie movement (LSD was made illegal across the United States soon after its release, and the film’s portrayal of it prompted the British Board of Film Censors to ban the movie for 35 years), the film’s thematic underpinnings still carry weight decades after the Summer of Love. As someone who doesn’t have any experience with such drugs, I was pleased that the film wasn’t an excuse for flashy imagery, and that it grounded the psychedelic experience in human drama through its focus on whether Paul can form personal connections amidst the emotional turmoil of a divorce. Among those The Trip impressed upon its initial release was a young film buff from Cincinnati named Tim Lucas…

The Author

A renowned film critic/historian with fifty years of professional writing experience, Lucas is best known for co-publishing (with his wife Donna) the pioneering home media review magazine Video Watchdog (1990-2017), and for writing the celebrated critical biography Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark (2007). He has provided audio commentaries on the DVD and Blu-ray releases of over 100 movies, covering not only most of Bava’s films and several of Corman’s, but works by directors as varied as Jean-Luc Godard, Alfred Hitchcock, Sergio Leone and Orson Welles. Lucas has also penned three published novels: Throat Sprockets (1994), The Book of Renfield: A Gospel of Dracula (2005) and The Secret Life of Love Songs (2021). A throughline that connects Lucas’ work is his focus on our capacity for experiencing and expressing love for each other. This is an appropriate motif, given the themes of Corman’s film and the story he has weaved about its creation.

In 2003, Lucas began writing a comical screenplay about the making of The Trip with his friend, writer/artist Charlie Largent. Their story was structured around Corman’s revelation that, despite not outwardly fitting in with the counterculture of the period, he prepared for the film by undergoing an LSD trip on the beaches of Big Sur, California, surrounded by colleagues who witnessed and recorded his observations.

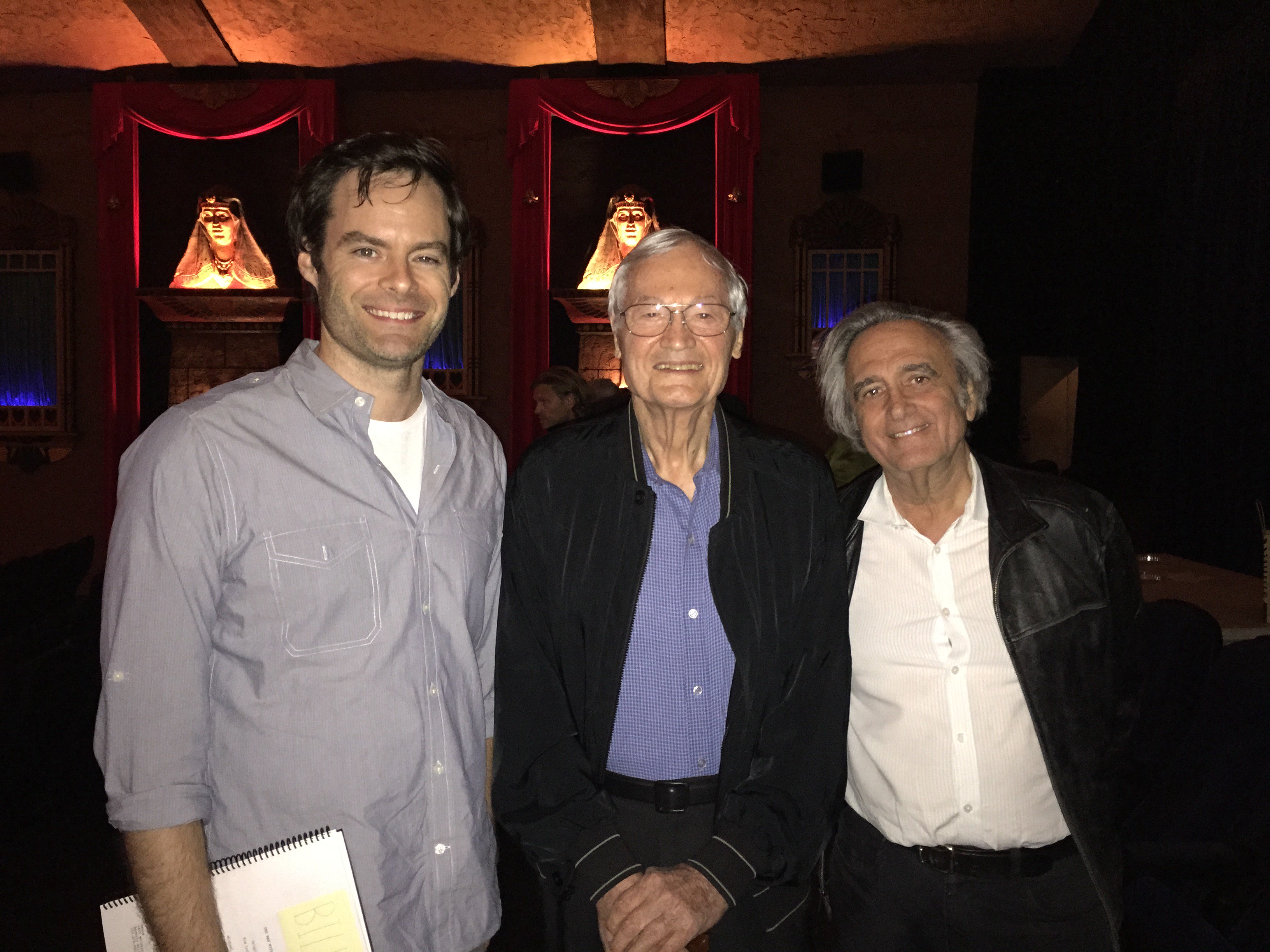

Although The Man With Kaleidoscope Eyes was soon optioned by Corman’s protégé, Gremlins (1985) director Joe Dante, and it is set to be co-produced by SpectreVision (Elijah Wood’s production company), the film has yet to see the light of day. The closest the project has come to being actualized was a 2017 script-reading at the Vista Theater in Los Angeles, billed as “The Greatest Film Never Made”; reviews of the reading unanimously praised Bill Hader’s portrayal of Corman. These aborted attempts to make the movie inspired Lucas to rewrite Kaleidoscope Eyes as a novel, drawing on correspondence with Corman’s wife/producing partner Julie, and his long-time assistant Frances Doel, to expand the story beyond what was in the script, which by this time had undergone several revisions, including contributions from writers Michael Almereyda and James Robison.

Commentary

Lucas’ earlier novels are characterised by their unconventional approach to narrative structure. Primarily written from the first-person point of view of the protagonists, they frequently take unexpected turns into other modes of writing, including transcripts of film scenes and interviews (Throat Sprockets); diary entries, letters and commentaries written by characters years after the referenced events (The Book of Renfield, in the style of Bram Stoker’s Dracula); and songs (The Secret Life of Love Songs).

The Man With Kaleidoscope Eyes continues this trend, albeit to a lesser extent than its forebears, by presenting its first four chapters out of chronological order, with chapter titles indicating the month and year in which the events take place: the story begins in November 1966, with Peter being awed by Jack’s script for The Trip, before flashing back five months earlier to Roger in the throes of post-production on The Wild Angels. It diverges from Lucas’ previous works by being his first novel to be largely written in a narratorial third-person style, with its only ventures into first-person occurring in Chapter 11, which chronicles Roger’s trip. As a reading experience, I would describe Kaleidoscope Eyes as Lucas’ most accessible novel, and appropriately his most cinematic.

As with his earlier books, Lucas demonstrates meticulous attention to detail: his vivid overview of the changing cultural landscape in mid-60s Hollywood in Chapter 2 (which he describes as “the Summer of Foreplay before the Summer of Love”) infuses the location with a sense of excitement, where anything is possible and change is the law of the land. His imagination is on full throttle in his renderings of Roger’s trip, which are appropriately thoughtful yet bizarre. Consider the passage where Roger’s musings over the grains of sand that comprise Big Sur’s beach evolve into the observation that “God was a surfer”.

Given the setting, comparisons to Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) and its 2021 novelization are inevitable (Lucas has revealed that Tarantino was among the first to read Kaleidoscope Eyes’ script, and quickly voiced his desire to play the role of Roger’s friend, screenwriter Chuck Griffith). Like Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which revels in its tributes to classic Hollywood TV shows, movies and Spaghetti Westerns, Kaleidoscope Eyes is full of references to Corman’s other films. These include his civil rights-themed drama The Intruder (1962) – the commercial failure of which makes Roger hesitant to make more “personal” films – and X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963), the poster art for which helps him devise an on-the-spot pitch for The Trip to his AIP bosses Sam Arkoff and Jim Nicholson.

I also spotted several funny references to The Little Shop of Horrors (1960): when Chuck tries to buy LSD from a dealer at Venice Beach, the dealer promises “Lots plants cheap”, a verbatim reference to a sign on Mushnick the florist’s wall, and Audrey Jr.’s catchphrase “FEED ME!” rears its head during Roger’s trip. The book is also packed with period detail (such as Metrecal, a predecessor to Sustagen that Roger drinks), and references to the music of such artists as Herb Alpert (“Spanish Flea”). As with the call-backs to Roger’s movies, these might throw off a reader unfamiliar with them, but Lucas’ fast pace allows 60s novices to get back on track to the heart of the narrative.

An advantage of the novel’s third-person approach can be seen in Lucas’ fleshing-out of the book’s cast. With a few exceptions, the supporting characters of his other novels tend to be abstract, in part due to the often-egotistical perspectives of the protagonists. Here, most of Roger’s friends and colleagues are clearly-defined, likable creatives who you want to see achieve success. Peter is a wide-eyed dreamer who wants to carve a legacy of his own, rather than simply being “Hank’s boy”. Jack is a hardworking, emotive artist who is frustrated by the bad hand life has dealt him thus far – his divorce from actress Sandra Knight inspires Paul and Sally’s split – but is determined to reward Roger’s friendship and trust.

Appropriate given her background and Oxford education, Frances is very much the Alfred to Roger’s Batman, a sounding board as much as she is a faithful assistant. Chuck – who recalls Harry Connick Jr.’s portrayal of Dean McCoppin in The Iron Giant (1999) – is a cool beatnik who happily guides Roger through his trip despite his initial 600-page script for The Trip being discarded in favour of Jack’s more streamlined take. Another of Roger’s protégés, Peter Bogdanovich – whose directorial debut Targets (1968) is prominently foreshadowed by Lucas – is a sharp-witted dandy keen to make the leap from critic to filmmaker. In their brief scenes, Bruce and Dennis are intellectual, curious thespians eager to give Roger their best work in their performances as John and Max, and while he does not turn her into a fully-fledged character, Lucas offers a nice appreciation of Salli and her portrayal of Glenn.

Whereas Lucas’ previous novels can be described as ranging between melancholic or tragic in tone, Kaleidoscope Eyes is the first to demonstrate his lighter side, imparting a sense of optimism that shines through the darkness. It shares a view with Once Upon a Time in Hollywood that, as long as you have friends in your corner and take risks, you can clear the hurdles Hollywood puts in your way.

What about Roger himself? Given the book’s generally light tone and its loving tributes to several celebrated talents, it might have been easy to make him an amiable everyman, a vehicle through which the story unfolds, but Lucas turns the maverick moviemaker into arguably his most complex protagonist yet.

In his audio commentary for Corman’s The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Lucas notes that the heroes of many of the director’s films are truth-seekers. This is an attribute that also describes the leads of Lucas’ prior novels, and one which he applies to Roger, whose persona is defined by his incongruities: he has the dress-sense of an old fogey, the mind of a businessman, the heart of an explorer and the soul of an artist. Despite his personal tastes not lining up with those of his younger hippie colleagues, he is determined to accurately portray the psychedelic experience with as much realism as possible in the confines of a low budget, consulting Chuck and Jack about their experiences with LSD and extensively reading the works of such proponents of the drug as Dr. Timothy Leary in preparation for his trip and the film informed by it. Roger’s various faculties come into play in not only how he conducts his work – he views himself as a problem-solver who wants to work out “how to turn $300,000 into several millions” – but his love life.

Reading through Lucas’ books, I have been struck by his consistent focus on the relationships between his main characters and the women in their lives. His stories cover a wide spectrum of how men interact with “the fairer sex”, including seeking a partner with mutual erotic interests (Throat Sprockets); experiencing the pain of unrequited love and the danger of seduction (The Book of Renfield); and discovering the duality between spouses and muses (The Secret Life of Love Songs). Here, Roger is depicted as a 40-year-old serial monogamist; although courteous and deeply attracted to women (“The Earth is a woman… and I am HUMPING HER!” he screams during his trip), he has trouble allowing them to embrace his multifaceted makeup. Despite having three different girlfriends over the course of the story, Roger’s behaviour is carefully portrayed by Lucas as not creepy or predatory, but indicative of someone who ends relationships as soon as it is clear they are not long-term.

Paralleling Paul’s conflicted feelings for Glenn in The Trip, Roger is unsure about the deepness of his friendship with Julie Halloran, a researcher who shares his passion for problem-solving. He deliberately falls out of contact with her while preparing for the movie, fearing that she would not approve of his own “research”. The manner in which Lucas resolves this will-they-won’t-they dynamic not only does justice to the climax of The Trip, but the union they would eventually share together.

Lucas delivers two symbolic masterstrokes during Roger’s trip, which serve to convey his attitude to life: the constant, heightened ticking of his watch, and a “journey” into a giant rabbit-hole covered by screens showcasing every movie that has been, and will be, made. Unlike Paul, who is subconsciously ashamed of the commercialism of his chosen profession, Roger (in both the story and real life) has always embraced the artistic and commercial aspects of filmmaking. His determination to take advantage of what time he has left (in typically punctual fashion for Roger, his trip ends ahead of schedule!) has led him to not only push boundaries in his own movies, but also foster promising talents who might not have otherwise gotten the big break they needed. Indeed, numerous graduates of Roger’s informal “film school” would go on to become Oscar winners, including Bogdanovich, Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Ron Howard, Jonathan Demme and James Cameron.

And the ending? Well, although you can already find out about it online (Dante has already shot part of it as a form of “insurance”, and Ozploitation legend Brian Trenchard-Smith has told me that he was involved as a stand-in), I encourage you to discover its power – it’s a provocative capper that’ll leave you with those burning questions I asked at the start of this deep dive. Without giving too much away, it also neatly harkens back to both the ending of The Book of Renfield, and a phrase Roger may (or may not?) have uttered towards the end of his trip. This line, in turn, is a reference to a phrase claimed by Stephen King to have been uttered by Ray Milland’s character in an unedited version of the ending to X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes…

A fun, hauntingly beautiful tribute to one of the great craftsmen of the film industry and the power of his work, The Man With Kaleidoscope Eyes earns my highest recommendation. I only hope it’s a matter of time before the rest of the movie version is made…

The Man With Kaleidoscope Eyes is available from PS Publishing at https://www.pspublishing.co.uk/the-man-with-kaleidoscope-eyes-hardcover-by-tim-lucas-5700-p.asp (print) and https://www.pspublishing.co.uk/the-man-with-kaleidoscope-eyes-ebook-by-tim-lucas-5829-p.asp (eBook).

The Trip can be rented on Apple TV+ and is available on Blu-ray from UK distributor Signal One Entertainment at https://www.signal1entertainment.com/products/the-trip-blu-ray.

Watch the trailer for The Trip here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWX_-rO-1nU